NPO Multi-Language Information Center Kanagawa

Largely based in Kanagawa Prefecture, NPO Multi-Language Information Center (MIC Kanagawa) has provided medical interpreter services since 2002. Currently MIC Kanagawa assists with approximately 7000 foreign language interpretation cases a year, covering 12 different languages including many Southeast-Asian languages. Interpreters are trained thoroughly before being dispatched to a medical institution.

Members of FIT For Charity Organizing Committee visited the MIC Kanagawa office to hear the stories of Executive Representative Mr. Katsumi Matsuno, Vice President Ms. Yoko Iwamoto, and English Interpreter Ms. Kei Tanaka.

(From left to right) NPO MIC Kanagawa Vice President Ms. Yoko Iwamoto, Executive Representative Mr. Katsumi Matsuno, and English Interpreter Ms. Kei Tanaka.

FIT: Please tell us how MIC Kanagawa began.

Matsuno: MIC Kanagawa officially kicked off in 2002, but Kanagawa volunteer center had been gathering interpreter groups and hosting symposiums since 1999. Many of the concerns raised during the symposiums were regarding the difficulty of medical interpretation and the lack of interpreters in the medical field. As a result, the symposium committee started a project to provide training for medical interpretation at the Kanagawa volunteer center. That marked the beginning of MIC Kanagawa.

Matsuno: I had been working as a medical care worker for over 30 years, but since 1990 I have been involved with tackling issues regarding medical services provided for illegal foreign nationals in Japan. Due to their status, they are not eligible to enroll in health coverage. Therefore, their medical fees are high and if they are admitted to a hospital, they are unable to pay the hospital fees. In the past, in some cases, the foreign nationals were able to receive help from public welfare. However, since 1990, addressing these issues became more difficult and incidents where foreign nationals refused treatment happened at several locations. I was surprised at the problem that people are able to receive free treatment if they don’t have money, but they couldn’t receive treatment if they didn’t understand what was being said to them. Coincidentally, it was around that time when I became involved with MIC Kanagawa.

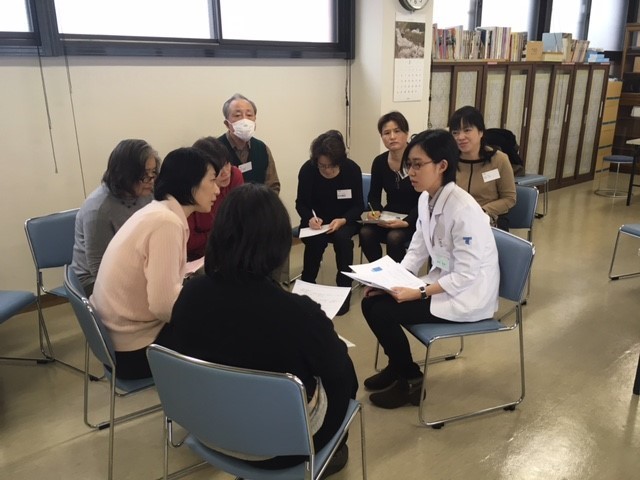

Currently at MIC Kanagawa, interpreters are trained and required to pass admission before being dispatched to medical facilities. The training focuses not only on language skills but also on communication skills.

FIT: Please tell us about the volunteers who participate in MIC Kanagawa.

Iwamoto: In addition to having a high level of language skills, our volunteers have a kind heart to help others. I believe most of our volunteers are Japanese nationals who have experience living abroad and after returning to Japan, they want to put their language skills to good use. Some of our volunteers are foreign nationals who themselves have experienced difficulties living in Japan and at Japanese hospitals. Having adjusted to life in Japan, they want to help other foreign nationals. We post ads for volunteers in Kanagawa’s PR magazines and receive inquiries from people who want to make a living as an interpreter. For a 3-hour interpretation service, we pay 3,240 yen in remuneration, which includes the volunteer’s travel expenses. Considering the high level of skills and expertise required in this field, it is clear that our payment is far less than what would usually be paid for the same level of service. However, the volunteers who understand our situation continue to provide their services nonetheless.

FIT: I would assume that there are many doctors who can speak English.

Tanaka: It’s true that many doctors can speak English and that is why we did not include English in our five interpretation languages (Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Korean, and Tagalog) when we first started our program. However, not all English speaking patients are from North America and some may speak the language with a very heavy accent. MIC Kanagawa’s services are utilized when such patients and doctors who are not used to hearing the accent are not able to fully understand each other.

Tanaka: At times, the volunteer interpreters may stay with the patient in the waiting room for up to 2 hours. During that time, the interpreter can become accustomed to the patient’s accent and learn about why the patient came to the hospital. Often times, the doctors may know the medical terminologies in English, but do not know how to communicate them in layman’s terms or the patient may be fluent in conversational English, but unfamiliar with medical terminology. In such situations, the interpreter volunteers can help break down the technical terminologies into simple words. Also, not all patients are highly educated.

Iwamoto: Since MIC Kanagawa started to dispatch interpreters, I feel that the attitude of doctors towards patients has also changed. For example, over 10 years ago when I was volunteering as an interpreter, I translated a technical terminology “pre-eclampsia” (recently called “gestational hypertension”) and when the patient did not understand the term, I asked the doctor to explain the term. However, because it was a commonly known diagnosis in Japan, the doctor was not used to explaining the term. The explanation turned into a discussion full of jargon, which I tried hard to interpret, and caused the patient to panic.

However, I feel that such situations have decreased and the ability of doctors and nurses to explain diagnoses have improved greatly. Doctors and interpreters cooperate more and are able to convey information in a way that the patient understands the situation correctly.

FIT: Please tell us what made you want to volunteer as an interpreter.

Tanaka: The experience of raising my child in the U.S. and going to the hospital frequently was a big part of why I joined MIC Kanagawa. My child became ill since second grade of elementary school but since I was ony able to speak conversational English, I had no problem communicating with the pediatrics doctor. However, when they were not able to figure out the cause of my child’s illness, my child was transferred to a university hospital. I panicked when I thought about how sick my child was to require such medical attention. The diagnosis was one that I had never seen in Japan. I was very anxious. The doctor was very kind and answered all of my questions. However, I could not help but feel that I would be able to ask more questions in Japanese. Since that day on and until we returned to Japan, we spent our days going back and forth to the hospital.

One day, I noticed a label that read leukemia on one of the many prescribed drugs and was distraught over the thought that my child was battling leukemia and people were withholding information from me out of sympathy. I had many questions I wanted to ask, like would there be any after-effect of my child taking so much medication, but felt helpless as I was not able to due to my lack of English skills.

Luckily, a drug that was not approved in Japan had worked and my child is now living a normal life. However, until we returned to Japan, our lives were closely intertwined with the hospital. After returning to Japan, I saw MIC Kanagawa’s ad recruiting volunteers for medial interpreters and felt that this was something only I could do from spending so much time at the hospital. Shortly after becoming enrolled, I learned that was that I was only well informed in my child’s illness but not much in anything else. Since then, I have been researching every day to expand my knowledge.

FIT: A big portion of interpretation services seem to be focused on obstetrics and gynecology. Please tell us why.

Iwamoto: Obstetrics and gynecology usually require multiple trips and thus many interpretation services. It is also a relatively calm environment, so it is suitable for new volunteer interpreters. However, there are first-time volunteers who went through the hard experience of interpreting a pregnancy failure. When it is a difficult diagnosis, multiple doctors may discuss the diagnosis before telling the patient. The interpreter may feel nervous during the discussion. However, it is important to stay calm as the patient may be feeling even more anxious. Peer support is necessary to prevent an interpreter from bottling up feelings after interpreting a difficult situation. Our volunteer interpreters can speak to our staffs as well as speak during peer counseling among the same language teams. Interpretation can be tough when you are very empathetic.

Matsuno: The patient may become dependent upon interpreter as they are relieved to finally meet someone who understand their language. If an interpreter gives his/her phone number to a patient, he / she may receive emergency phone calls in the middle of the night and it becomes difficult to respond to all inquiries. Hospitals often ask that we send the same volunteers, but the coordinators must make sure to be in line with the prefecture’s objective to have as many people experienced in interpretation as possible when deciding which interpreter volunteer to dispatch. When the case or diagnosis is complicated, having a new volunteer interpreter every time may cause problems, so we may dispatch the same three volunteers to take turns.

FIT: Please tell us about any memorable episodes.

Matsuno: I would like to talk to you about a fourth grade Peruvian girl. Peruvians living in Japan have formed a closely knit community so that Peruvians can go on about their lives without learning Japanese. However, the Peruvian children attend Japanese schools, so they grow up to be bilingual in Japanese and Spanish. A Peruvian mother who was not fluent in Japanese had gotten sick and her condition had not improved for a long time.

She usually visited the hospital with her daughter, who acted as her translator, but a volunteer interpreter was dispatched from MIC Kanagawa when the daughter was not able to attend due to school. When the mother heard the explanation from the interpreter, she found out that it was different from what her daughter had told her. As it turned out, the daughter felt sorry for her mother, and could not bring herself to tell her the truth. Once the mother heard the correct diagnosis, her condition improved right away. The experience made me realize that it is important to interpret from a fair standpoint.

Iwamoto: These situations happen all the time. I joined MIC Kanagawa through a volunteer group that I translated / interpreted for in my home town. At times, the responsibility of the volunteers came into question. When I used to volunteer for a foreign national mothers’ association at the public health center, a mother asked us to come with her to the hospital to help her understand why the doctor had suggested for her to undergo a surgery. However, we were worried that we would not be able to take responsibility if anything goes wrong with such a difficult interpretation such as explanation of a surgery without adequate training. The mother eventually had her seventh grade niece come along with her. Although these problems are gaining more attention, many people are still unaware so an organization based in Kobe has been trying to spread awareness by distributing DVDs of the difficulties faced by foreigners receiving medical care in Japan.

FIT: How is the home medical interpreter dispatch service progressing that started last year?

Matsuno: Although there have been several inquiries about the service this year, to be honest we have not been able to make much progress. We are currently considering what the best method would be to spread the word regarding the service. At first, we were thinking about home health care, but because foreigners are also aging with the population of Japan, we are planning to also focus on nursing care services and preparing for inquiries from nursing care establishments and Regional Comprehensive Support Center. We believe it is part of an information service necessary for our daily lives.

FIT: Is the interpreter dispatching business getting institutionalised, or have there been any policies built around it?

Matsuno: In principle, dispatches to medical institutions in Kanagawa prefecture are becoming institutionalised. So far 36 medical facilities have become official partners. Currently, remuneration is paid to each interpreter by the hospitals, but MIC Kanagawa does not receive any payment. As the number of interpreters increases, we will become busier. We believe this is the blind spot of this business. Our goal is to grow these services into a permanent system so that other communities can also institutionalize and provide the same types of services.

FIT: Thank you very much for your time!